As all eyes zoom in on disaster struck cotton crop, concerns regarding fiber import bill are taking root. Last year, Pakistan’s spinning industry had imported cotton worth $1.82 billion, a record import bill even as volume imported fell by almost 0.5 million bales. Early estimates suggest that the ongoing marketing year won’t turn out to be much different.

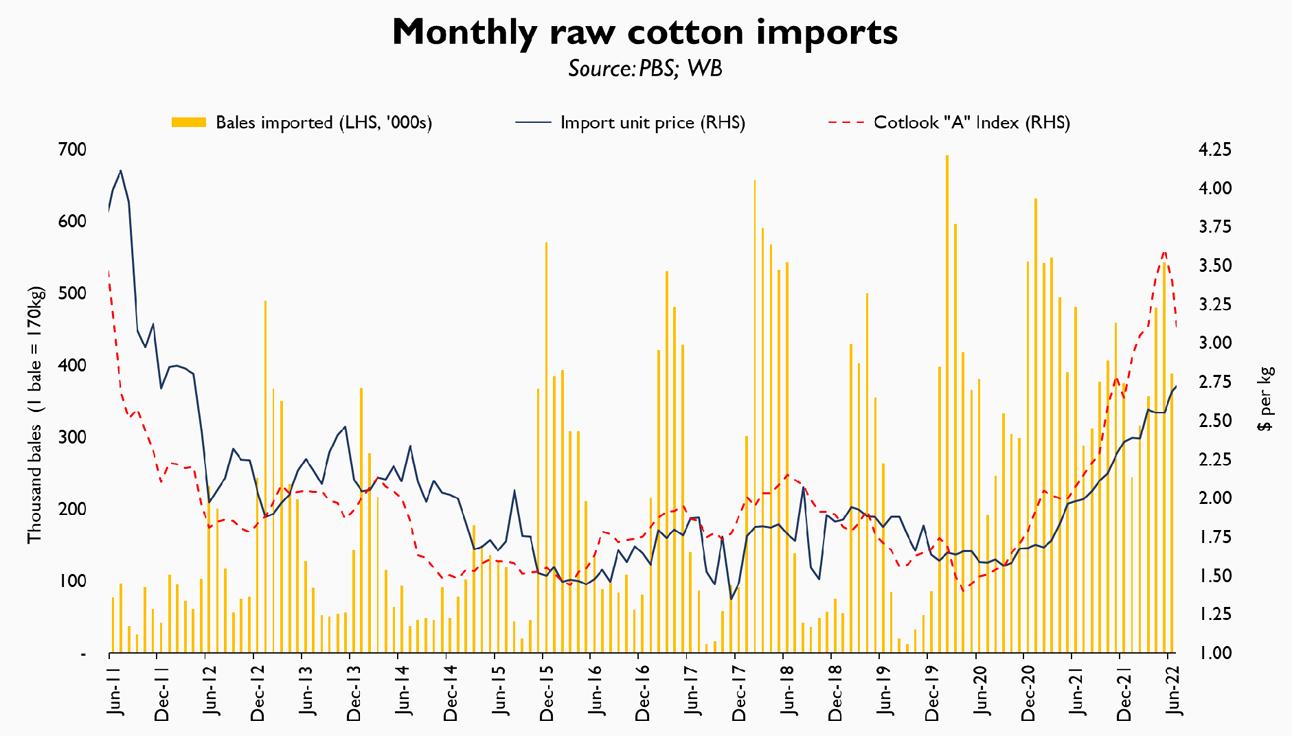

Cotton import volume fell during FY22 to 4.55 million bales as industrial demand moderated in response to escalation in prices. Average unit price of imports rose to $2.36 per kg, up 36 percent compared to $1.73 per kg the preceding year when Pakistan had imported a record volume of 5 million bales. Incidentally, this was the first time since FY11 when unit price of imports rose above $2 per kg, after a decade of international market prices remaining rangebound between $1.5 and under $2 per kg.

It is hard to imagine if things will take a turn for the better during FY23. Already during the first two months of ongoing fiscal, cotton import bill is up 23 percent, even as volume imported fell by 12 percent year on year. Even the best-case scenarios – including BR Research’s – expect local production to be shaved off by at least a million bales, if not more. Yet, that may fail to translate into substantial rise in import quantum, as Pakistani buyers may find themselves priced out in the international market.

For two reasons. First, it is important to remember that even before floods had hit Pakistan’s cotton acres, the country had cemented its place as world’s fourth largest cotton importer, behind China, Bangladesh and Vietnam. Meanwhile, ban on Indian imports, coupled with massive crop abandonment in USA – which is Pakistan’s largest supplier – means there weren’t many willing sellers in the international market to begin with. Now, the damage from floods has further exacerbated the domestic shortfall by at least a million or a halfbales. The only other two major exporting sources are Brazil and Australia, where most suppliers are already tied into exporting contracts with Chinese, Vietnamese, and Mexican firms.

Which brings us to second reason: pricing. A tight international market – coupled with the Xiangyang situation – means that world prices have very little cause to drop further substantially, despite recessionary headwinds dampening textile demand in developed markets. Going forward, if unit prices of imported cotton averages above $3 per kg for rest of the year, Pakistani textile manufacturers’ limited pricing power in the international market means they may begin to lose buyer interest, unless of course the industry braces itself and risks reduced profitability in exchange for long term supplier relationship and trust.

If world cotton prices remain elevated for better part of the fiscal, history suggests import demand may only witness subdued growth despite supply deficit back home. At projected imports of 5.5 million bales – one million more compared to last year – Pakistan may have to pay as much as $2.8 billion in precious foreign exchange. Whether the additional billion dollar spent on importing fiber will bring in timely and commensurate forex in the shape of exports is any body’s guess. With energy prices also witnessing runaway inflation, would the country be better off importing yarn instead? (As raw material for made-up textile manufacturing). Policymakers could have looked in that direction, were it not for the Rs100 billion+ TERF funds loaned out to prop up a dated industry.