An idea of how precarious the food situation has tended to become for hundreds of millions of people in the world's poorest countries has been revealed in the Food and Agriculture Organisation's report on the "State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2004." For, it has pointed out that the queer combination of trade barriers, subsidies in industrialised nations, along with a 40-year decline in real prices of commodities, had been sapping the only source of cash income for many of the 2.5 billion people in developing countries who owe their subsistence largely to farming.

Moreover, tracing their predicament to subsidies in Western Europe, the United States, and other wealthy nations - along with tariffs on agricultural imports in both rich and poor countries - it blamed these for causing severe distortions in world markets and farm trade.

Again, pointing out that some 230 billion dollars in support paid to farmers in wealthy countries added to the burden of declining commodity prices, thus also threatening the livelihood of the poor farmers in affected countries. It also noted that support for farmers in industrialised nations came to the equivalent to 30 times the amount provided as aid for agricultural development in the poorer countries.

More to it, it also observed that as agricultural commodity prices had plunged to their lowest since the Great Depression of the 1930s, subsidies had further added to the squeeze, thereby, adversely affecting developing countries that have been desperately trying to export commodities like cotton, sugar and rice.

According to the evidently, disquieting, FAO report, over 50 developing countries, including most of the poorest ones, depend on exports of up to three farm commodities for 20 to 90 percent of their foreign earnings. For these people, it said, developments on international commodity markets would literally spell the difference between feast and famine.

For, as it explained, the least developed countries had also found their share of world agricultural trade shrink, while losses of income and employment caused by falling prices outweighed any likely benefits to the vast majority of the poorest among their consumers.

As against this, it has also noted that the main beneficiaries of lower food prices have been the consumers in the developed countries, as well as of the slowly urbanising areas of the developing countries.

Generally speaking, all this, put together, should bring to the fore, only seemingly marginal gains for such developing countries engaged in boosting their agricultural economies through diverse efforts as focusing improved productivity, on the one hand, and laying greater emphasis on value-addition though food processing, on the other.

For the revealing report also has it that tariff barriers, as surrounding major consumer markets had also hampered attempts by a number of developing countries to expand exports of processed foods and by developing domestic food industry too.

Mention, in this regard, may also be made of the minor difference made in the plight of the disadvantaged developing countries through the help from certain multinationals to some small-holders to move into the world markets and to modernise production technology in certain poor countries, thereby, assailing "market power in some commodity supply chains of large transnational corporations for failure in such efforts.

For as the report has noted, three companies now account for almost half the coffee roasting in the world, as 30 supermarket chains control "almost one third of grocery sales world-wide." All in all, the prospects of the world's predominantly agricultural economies, inhabited by large bulks of poverty-stricken millions, will appear to be quite bleak, notwithstanding their increasing emphasis on development efforts to the accompaniment of social and political reforms on western lines.

Little wonder, while objectively analysing the plight of the agricultural economies of the potentially rich poor countries of the world, the FAO has rightly urged the World Trade Organisation to bring an expeditious end to the variously troubled agricultural talks in such a manner as to facilitate developing countries' access to the world markets.

The plea, in this regard, will be seen as punctuated by a warning that in the case of cotton, sugar, rice and dairy products, farmers in the EU and the United States, who have benefited all this long from huge subsidies, could eventually stand to lose, in case the needful is not done in time.

Meanwhile, WTO chief Supachai Panitchpakdi is reported to have simultaneously told a meeting of the organisation's Trade Negotiating Committee that they must get down to hard bargaining immediately if a 2006 target for a free trade pact is to be met.

Moreover, as a report from Geneva indicated, negotiators appeared to agree that a detailed blueprint in the key areas of farm and industrial goods trade, with significant advances also in negotiations on services and in other issues, must emerge from next December's ministerial meeting in Hong Kong.

It will be recalled that the WTO's Doha Round, which was launched in 2001 to give a boost to the world economy, should have been wrapped up by end of 2004, which has not happened.

For deep differences between rich and poor, particularly over agriculture, hampered progress in the early years. Hopefully, Panitchpakdi has reportedly stressed that in Hong Kong, members must agree on specific targets for slashing subsidies and opening up markets for agriculture and industrial goods.

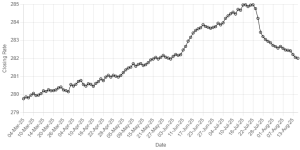

BR100

15,103

Increased By

140.9 (0.94%)

BR30

42,619

Increased By

540.8 (1.29%)

KSE100

148,196

Increased By

1704.8 (1.16%)

KSE30

45,271

Increased By

438.2 (0.98%)

Comments

Comments are closed.