Ethiopia's elections are the furthest thing from Bisharo Sultan's mind. As politicians wrangle over privatisation, land reform and the constitution hundreds of kilometres away in the capital Addis Ababa before polls on Sunday, Bisharo wonders how she will feed her four children. A herder who wandered the plains in search of watering holes in Ethiopia's eastern Somali region, Bisharo lost 200 camels, cows and sheep to the country's chronic cycle of droughts. A flash flood last month wrecked her makeshift house in the Hartishiek camp where 6,000 people live without running water, hospitals, or schools and where there is scant help on offer.

"It's as if we're the forgotten people," she said, suckling her one-year-old son - his swollen head a tell-tale sign of malnutrition. "I expect the government to solve my problems but I don't know the government. I haven't seen them."

The polls are regarded as an important test of democracy after centuries of feudalism then years of Marxist dictatorship under Mengistu Haile Mariam, overthrown by Meles in 1991.

But voters from among 4.5 million people in the Somali region - one of nine ethnically based federal states - will cast their ballot three months after the rest of the country, well after official results of the national polls are announced.

Their votes will determine the make-up of the Somali state's regional assembly, but will have no impact on the national parliament in Addis Ababa that chooses the prime minister, deepening the inhabitants' sense of marginalisation.

Government officials attribute the delay, which also took place in previous national elections, to the vast region's inaccessibility, nomadic population and floods.

Many in Hartishiek do not care much whether Meles, a man from Tigray in the distant north, wins a third five-year term in office; they are more worried about whether their regional government will resume distributing food.

Camp dwellers say the rations were stopped months ago because officials want the herders to pack up and leave the camps, which have become a burden for local authorities.

"Our lives are terrible," Bisharo said.

She now makes mats to sell for five birr ($0.6) a piece, enough to buy a gram of sorghum or maize. When that runs out after a couple of days, she feeds the children water.

It is perhaps not surprising there is a lack of interest and some scepticism over political wrangling in Addis Ababa among rural Ethiopians, who represent more than 80 percent of the country's 71 million people.

In the countryside, the officials who count are those that govern the woreda - or district - and are responsible for irrigation projects and handing out fertiliser, rather than members of the national assembly.

Mohammed Sheik Abdel, of the government Disaster Prevention and Preparedness Bureau, admits that local officials siphoned off up to 10 percent, or 2,000 tonnes, of the United Nations' monthly cereal distribution to the Somali region.

"Transporters themselves divert it and give money to local administrators or local administrators misuse it," he said.

UN officials estimate that more than 360,000 Ethiopian children are likely to suffer severe malnutrition in the next few months, many of them in the Somali region where hunger is a more pressing issue than voting.

"We have heard there are elections but it doesn't concern us. The hungry person cannot understand them," said elder Shafi Nour. "We beg Allah to change our future for the better with these elections."

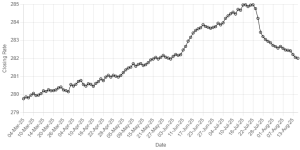

BR100

15,186

Increased By

82.6 (0.55%)

BR30

42,842

Increased By

223 (0.52%)

KSE100

149,361

Increased By

1164.3 (0.79%)

KSE30

45,552

Increased By

281.7 (0.62%)

Comments

Comments are closed.