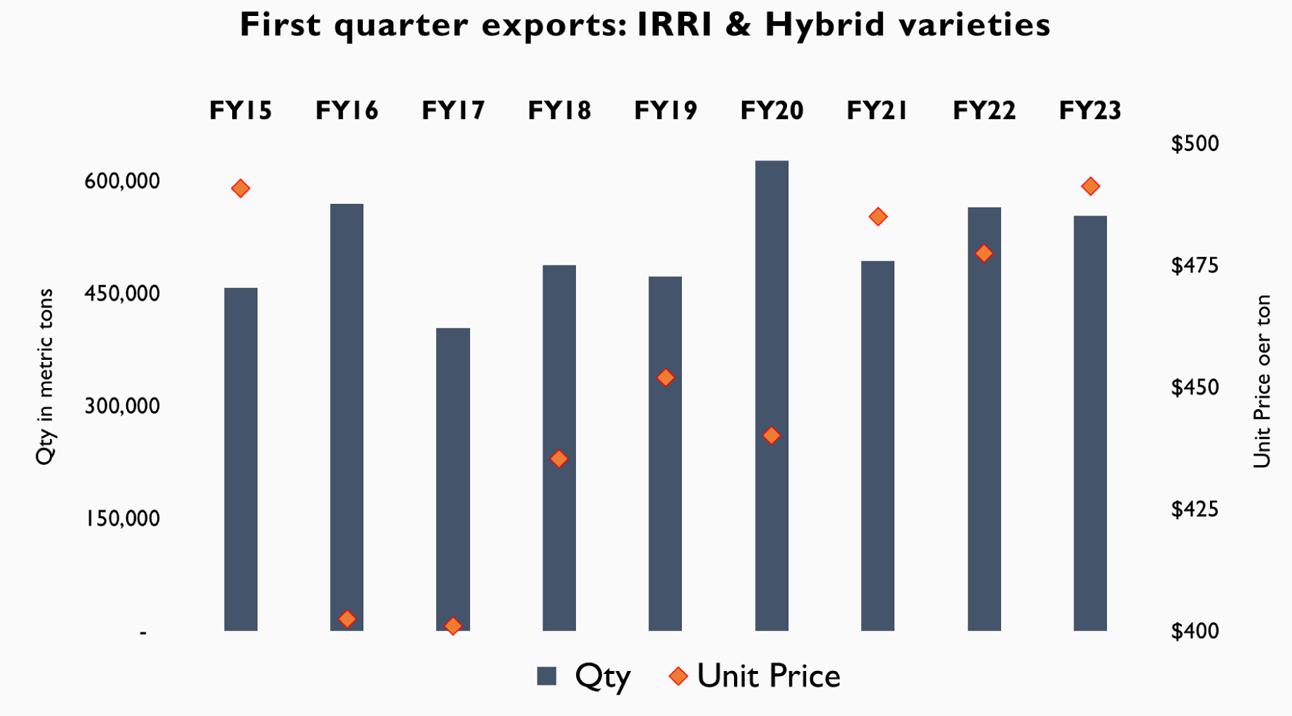

Pakistan’s rice exports are off to a bumpy sta-rt. After a stellar FY22 marking record growth in quantity exported and earnings, Q1-FY23 report card spells trouble. Headline numbers indicate a 9 percent decline in volume and over 5 percent fall in revenue, even as prices fetched in the international market held their ground. Are rice exports witnessing reversion to mean after hitting peak last year, or is there more at play?

For natural reasons, first quarter is usually slow for rice exporters. Clarity over new crop outlook is only achieved in earnest by late October/mid-November, once harvest is completed in Punjab. Historically, basmati exports during Q1 make up no more than one-fifth of annual export quantum; whileQ1 accounts for no more than 15 percent of annual coarse exports.

But the slowdown during Q1-FY23 is not just in keeping with past tradition. At nearly 30 percent lower than Q1-FY22, basmati exports are lowest in four years (minus Covid year). This comes despite a 55 percent rice in basmati prices in the international market compared to past season (3M average Jul-Sep). Pakistani exporters also fetched 20 percent higher prices compared to last year yet failed to export more volume. Now, prices are in fact receding in the international market, while currency has begun to stabilize (which risks eroding exporters’ margins). Have Pakistani exporters missed out on a golden opportunity by waiting too long?

BR Research has previously explained that unlike India, basmati variety is grown in Pakistan primarily for local consumption, with exports accounting for no more than 15-20 percent of local output. Since April 2022, prices of most domestically produced basmati varieties have shot up by as much as 30 percent in the local grain markets, led in part by poor wheat crop in the past season. In addition, Pakistan reported a 10 percent decline in basmati production last year (FY22), as a result of a misguided policy to encourage coarse rice production under the previous government.

And all of that came in to play long before the devastating floods that hit the crop in Sindh and Balochistan between Jul – Sep. With rice crop in the southern provinces devastated, Federal Committee on Agriculture estimates that national rice output would be at least 40 percent lower than last year, or 3.8 million metric tons lower!

Does this mean rice processors are going slow on exports in national interest and to ensure domestic food security? Although that charitable explanation may be appealing to some, it doesn’t explain the trend in coarse rice exports during Q1-FY23, where the slowdown was much more muted in comparison.

In fact, the explanation falls apart when one considers that the lost acres of Sindh had almost exclusively planted coarse rice varieties whose volume is in lockstep with recent trend. It may be worthwhile to note that coarse rice varieties have recorded no more than 10 percent rise in prices in the international market, and prices fetched by Pakistani exporters remained broadly unchanged compared to the previous year (3M average, Jul-Sep).

It is almost certain that exports during FY23 will fall significantly short of last year levels. However, exporter behavior appears vexing, especially given severe concerns over land available for wheat plantation during the upcoming rabi season. Are rice processors betting on a severe domestic grain shortage? Or, is the international market in retreat even though prices don’t signal as much just yet? Rice export trend remains one to watch closely over coming months.

Comments

Comments are closed.