Some French teenagers who are heavy smokers of cannabis are being offered a stark choice in a campaign to get them off drugs - counselling, or expulsion from school. Christophe is one of them. He is sulky as his mother escorts him into the Caan'abus centre in the south-western city of Bordeaux, one of only around 20 in France. "He's 17, and he's been smoking dope for two years now," his mother said. "We're at the end of our tether. We wanted to send him to see a doctor, we tried to talk to him ... he rejected everything.

"His marks at school are catastrophic, and last week he was picked up by the police because he was smoking a joint just outside school."

The Caan'abus centre has been receiving phone-calls virtually non-stop since the government launched a 10 million euro (13 million dollar) campaign at the beginning of February to warn of the harmful effects of cannabis on physical and mental health.

With more than one in five 18-year-old boys claiming to be regular users - and more than half of all 17-year-olds having smoked cannabis at least once - France has the highest consumption rate in Europe along with Britain and the Czech Republic, according to official figures.

Toxicologists say the cannabis now being smoked is far stronger than it was in the "flower power" days of the 1960s and 70s, and that it can induce memory loss, concentration lapses and alienation, and even contribute to triggering schizophrenia.

The Caan'abus team - four educationalists, two clinical psychologists, one doctor and one health counsellor - see teenagers by appointment, but also attend to those who just turn up.

Some have been referred by their schools or the justice system, but others arrive of their own accord. Caan'abus is hoping that the campaign will prompt others to turn to them rather than resort to the more common practice of expelling pupils.

Christophe and his mother were seen by Dr Marie-Regine Fried, together to start with, then separately.

"The most important thing is listening," the doctor said.

"We try to discover what the youngsters want; we try to make them realise what it's all about, to make them understand that once the euphoria has dissipated the after-effects arrive."

Educationalist Pierre Barc said: "We don't moralise, we don't criticise, and we don't sit in judgement we try to understand and to treat the causes."

He is not surprised that the two teenagers who had appointments with him that day turned out to be no-shows.

He fills in the time by manning the telephone.

The centre had treated some 200 cases over the previous two years, but the Caan'abus hot-line fielded 26 calls the morning the government campaign was launched.

"No, Madame, we don't do house-calls, but you can come here any time we're on duty," Barc told a caller worried about her son.

Christophe said he would rather be "with my mates", but added he understood that his parents are worried by his behaviour.

Since he started smoking cannabis, he acknowledged: "I do less, and I've been getting bad marks at school."

The doctor, after Christophe and his mother leave, said: "We haven't won that one yet ... I'm not sure he'll be back."

The first battle to win, for the Caan'abus team, is ensuring, after the obligatory first interview, that the youngsters return because they want to, and that they end up deciding themselves to give up cannabis.

"Some who return", said Fried, "need someone who will listen to them, an adult who is neither a parent nor a teacher, so that they can talk through their problems, because adolescence is a painful transition."

The Caan'abus team hope that the government campaign, which includes advertising spots on radio and television, will help make cannabis less of a run-of-the-mill product.

"In Bordeaux," said Barc, "it's as easy to buy a joint as to buy a loaf of bread.

"In the intermediate schools, just as in the secondary schools, you just have to turn around to find a supplier. Some of the kids don't even know it's illegal."

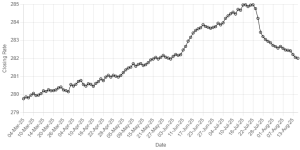

BR100

15,186

Increased By

82.6 (0.55%)

BR30

42,842

Increased By

223 (0.52%)

KSE100

149,361

Increased By

1164.3 (0.79%)

KSE30

45,552

Increased By

281.7 (0.62%)

Comments

Comments are closed.