Latvia's president leans forward in her chair in Riga castle, her 14th century official home, to emphasise a point in a history lesson that has sparked fresh tensions in the Baltics and a diplomatic row with Moscow. President Vaira Vike-Freiberga has joined other world leaders in accepting an invitation from Russian President Vladmir Putin to attend celebrations in Moscow on May 9 commemorating the 60th anniversary of Nazi Germany's defeat. But she also issued a communiqué saying the fall of the Nazis did not result in the liberation of Latvia.

"Instead the three Baltic countries of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania were subject to another brutal occupation by another foreign, totalitarian empire, that of the Soviet Union," it said. She told Reuters in an interview that her statement was a necessary and timely history lesson for Russia and the world.

"There was to me a need to come out with a reminder of ... our dissatisfaction with the interpretation that Russia was spreading about this event right now," she said.

Her agreement to come to Moscow was meant to improve ties with Latvia's former ruler even as Riga turns increasingly westwards. Instead her letter, which was also sent to Putin, has revealed Latvia's simmering distrust of Russia.

Moscow responded angrily to Vike-Freiberga's declaration.

"It gives the impression Ms Vike-Freiberga is deliberately provoking Moscow into withdrawing the invitation and ... as the president herself hints, into denying her a visa," Viktor Kalyuzhny, Russia's ambassador to Latvia, told Reuters. The escalating row shows what powerful emotions World War Two and its aftermath stirs in the Baltic states which, despite their rapid economic growth since independence in 1991 and their membership since last year of Nato and the European Union, are still haunted by decades of post-war Soviet rule.

In Riga's old town the national radio building bears the scars of shellfire, there is an occupation museum witnessing the enforced rule by the Germans and Russians and outside the capital there are memorials at concentration camp sites and Jewish killing fields.

Older people have especially long memories and grievances in countries which won for themselves short-lived independence in the 1920s and 1930s, only to see that wrested away when they were annexed by the Russians in 1940.

Some Riga citizens initially greeted the German army, which subsequently invaded, not with bullets but with flowers.

"The Soviets killed thousands. The first mass graves were created by the communists in their first year in Riga," said Latvian member of parliament Paulis Klavins, a 77-year-old who fought for the Germans. "Our people didn't know who Hitler was. If the Devil had come in tanks we would have greeted him as a liberator."

But when the war was finished and the Russians returned they deported more than 42,000 Latvian men, women and children to Siberia where many died. The exact number is not known.

For outsiders it is difficult to see how anybody could openly support the German army and local men who fought in it.

But in Estonia a statue of a soldier in German uniform, commemorating those who fought against the Soviet army, was taken down only last August under pressure from Jewish groups.

Symbols remain targets for pursuing grudges. In Riga, the defacing of a Russian war memorial drew protests from Moscow.

In accepting Putin's invitation, Latvia's president -- a retired academic born in Riga and in the post-war chaos grew up in German refugee camps -- extended "a hand of friendship".

But her move broke ranks with the presidents of Estonia and Lithuania who have been agonising about whether to go. They had a pact to reply jointly and there were angry words.

"Participation at Russia's victory parade where hymns to Stalin will be sung ... would be confirmation that Russia's arrogant and un-European stance is a correct one and that we are submitting to it," said Lithuania's former head of state Vytautas Landsbergis. He says the Latvian leader was "misled".

Younger Baltic people say that as the war and rule by other regimes recedes into the history books, the fractious relations with Russia, which still has close economic links and sends oil exports through the region, must improve.

Complicating that process -- in Latvia especially -- is that of society retains close ties to Moscow. In Riga, native Russian speakers comprise half the population. Many older ones do not even speak Latvian and do not have Latvian citizenship.

"Vladmir Putin is a good man and our strong leader," said Helena, a Russian-speaking Rigan businesswoman in her late 30s. "Why do I need to speak Latvian? Everyone here speaks Russian."

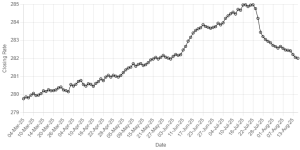

BR100

15,103

Increased By

140.9 (0.94%)

BR30

42,619

Increased By

540.8 (1.29%)

KSE100

148,196

Increased By

1704.8 (1.16%)

KSE30

45,271

Increased By

438.2 (0.98%)

Comments

Comments are closed.