A latest study conducted by Integrated Regional Information Network (IRIN), an information unit of United Nations, suggest that the number of street children in Pakistan is on the rise. It is believed there are some 70,000 children living on the streets nation-wide. Estimates that put the number of children living on the streets of Karachi at 8,000 in 2003, place the latest figures at closer to 12,000, an increase of 50 percent. The Lahore is estimated to have 7,000 children living on the streets while in Peshawar there are a further 5,000, another 2,500 in Quetta and 3,000 in Rawalpindi.

"The situation with regard to street children in the city is getting worse. The numbers are multiplying," Naveed Khan, chief executive officer for the Azad Foundation, a Karachi-based NGO, told

IRIN. The Azad Foundation has been working to raise the profile of street children in Pakistan for the last five years.

According to the NGO statistics, in Karachi 54.1 percent of the street children left their homes between the age of 10 and 12.

They also estimate that 45 percent of street children are involved with criminal activity in order to survive while 49 percent are at a high risk of HIV/AIDS through intravenous drug usage and sexual abuse.

But accounting for such a complex problem in Pakistan's largest city is not easy. Poverty is the driving force behind the phenomenon, followed by domestic physical and mental abuse, along with peer pressure and drug abuse.

"These are the key factors that lead children to begin a life on the streets," according to Farah Iqbal, Azad's research head and a trained psychologist at Karachi University.

Whether for economic or social reasons, street children leave their homes to live in parks, doorways, under bridges or in the open air.

Many find work collecting waste paper, cleaning cars, working as shoe shiners or in small hotels selling water, newspapers or other cheap items. Some resort to begging, pick-pocketing or solicit themselves for sex, while others end up as drug addicts.

They use inhalants which are cheap and easily accessible but which cause irreversible brain damage as well as a host of physical debilities.

"They abuse solvents more than drugs, such as glue," Iqbal said, because of the cheapness. Yet the problem of street children goes far beyond solvent abuse.

They have no access to basic amenities such as health, education or food.

The back streets of Karachi's bustling Sattar district is filthy and permeated by the stench of urine. Yet here children as young as five, huddle in groups of eight to 10 for warmth and security at night.

Street children are easy prey for those feeding on their innocence.

And with numbers increasing each year, so too do reports of physical and sexual abuse.

According to Azad, four out of every 10 street children examined were infected with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Sexual abuse is not uncommon. Many street children offer to provide a 'massage', a euphemism for sex, for as little as a dish of rice.

It is this that prompted Azad to open the Dastak drop-in-centre for street children in Sattar. It is the only facility of its kind and they can receive rudimentary health care, a hot meal along with basic reading and writing tuition. Perhaps more importantly they are also offered moral support.

"Basically, we try to introduce life skills to them and eliminate anti-social behaviour," Amjad Rasul, Dastak's programme manager, said. "They have negative attitudes towards society and need our love and affection."

In a further effort to reach the children, a mobile dispensary, complete with a doctor, visits areas where street children are known to congregate.

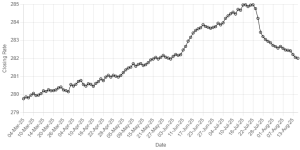

BR100

15,103

Increased By

140.9 (0.94%)

BR30

42,619

Increased By

540.8 (1.29%)

KSE100

148,196

Increased By

1704.8 (1.16%)

KSE30

45,271

Increased By

438.2 (0.98%)

Comments

Comments are closed.