The government's decision, announced with full fanfare on March 2, that oil price fixing powers would be transferred from OCAC to Ogra from April 1, has apparently run aground. Petroleum Ministry sources, quoted in a Recorder Report, have disclosed that instead of actually fixing the oil prices, Ogra's role will be confined only to "vetting" the prices already determined by OCAC.

What Ogra's "vetting" would actually involve is not clear yet. All this is bound to generate a perception that no material change in the existing mechanism is going to take place, and only a "cosmetic" measure was initiated by the government to placate the public hit hard by inflation triggered by runaway oil prices.

A second snag, mentioned in this context, is that Ogra officials would need some time to understand the formula used for fixing oil prices before they are able to perform their assigned duty.

This can clearly lead to further delays in the implementation of the policy decision, giving the OCAC and the Ministry of Petroleum a free hand till Ogra personnel have grasped the intricacies of oil price fixing mechanism.

Why no arrangements were made by the government for imparting the required training to them, after it had announced the schedule for transfer of powers nearly a month ago, is quite puzzling.

Further, as there had already been numerous representations and petitions against the "arbitrary" oil price increases, it was almost a foregone conclusion that the government will have to take some measures to placate public opinion.

Is the government's failure in arranging technical training to Ogra personnel an act of omission or commission? A possible way out of the dilemma will be for Ogra to hire the services of specialists in the field.

Why the OCAC, a private grouping comprising heads of nine oil marketing companies with no public representation, was assigned the role to fix petroleum prices, is yet to be explained by the government. Last year the World Bank had asked the government to assign the job to an independent body outside the Oil Ministry, and also rationalise the whole mechanism, which gave the "appearance of a collusion" between the government and the oil industry.

The Bank had also told the government that price fixing by OCAC "would be considered illegal in many countries of the world." Fuel prices in Pakistan have registered an increase of over 500 percent since the early 1990s, and a major part of the profits made by the oil companies may well have been due to inventory gain because of a galloping increase in oil prices.

In a petition filed in December last year, a consumer had demanded dissolution of OCAC and also the recovery of some five billion rupees allegedly accumulated by it through oil price increases.

The petition in effect sought to show that there was more to the oil price increases than met the eye. It should be mentioned here that the World Bank has been funding a $3 billion energy sector restructuring programme in Pakistan, and is keen to see oil and gas sector regulation transferred to Ogra, an autonomous body with adequate public representation.

The modus operandi employed by the government in this matter is also in contravention of the procedural parameters laid down by the Asian Development Bank, which clearly state that it is the "regulator" that should determine the prices. Simply "vetting" the prices fixed by OCAC will not conform to this criterion.

As oil price hike is a matter of direct public concern, it is suggested that regular public hearing be held to get popular feedback before a raise is effected. This will also help the authorities to determine the exact quantum of increase, in accordance with the practice in the civilised world in matters of direct public interest or concern.

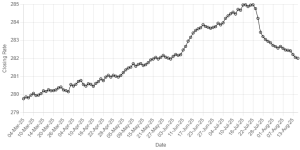

BR100

15,186

Increased By

82.6 (0.55%)

BR30

42,842

Increased By

223 (0.52%)

KSE100

149,361

Increased By

1164.3 (0.79%)

KSE30

45,552

Increased By

281.7 (0.62%)

Comments

Comments are closed.