Shariah Compliant Liquidity Management: Initially the major Islamic finance activity involved wholesale operations, with banks in London providing overnight deposit facilities for the newly established Islamic banks in the Gulf.

These Islamic banks could not hold liquid assets such as treasury bills, which paid interest, but the joint venture Arab banks in London, such as Saudi International Bank and the United Bank of Kuwait, accepted deposits on a murabaha (mark-up) basis, with the associated short term trading transaction being conducted on the London Metal Exchange.

Although the staffs of the joint venture banks were mainly British and non-Muslims, they became increasingly well informed about Shariah requirements regarding finance, and were able to respond to the demands of their Muslim clients in an imaginative manner.

There was considerable interaction between British bankers involved with Gulf clients, Shariah scholars and the British Pakistani community, notably through the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance (IIBI), that had been established in the early 1990s by Muazzam Ali, a former journalist and head of the Press Association of Pakistan.

Muazzam Ali worked closely with Prince Mohammed Bin Faisal of Saudi Arabia, a leading advocate of Islamic finance, and became Vice Chairman of Dar Al Maal Al Islami in Geneva, the international Islamic finance organisation established by Prince Mohammed in 1982.

The IIBI was initially located in the Kings Cross area, near to the City of London where the Arab joint venture banks operated, and in the late 1990s moved to more prestigious premises in Governor Crescent in the West End of London.

THE AL BARAKA INTERNATIONAL BANK The next milestone in 1982 was when the Jeddah based Al Baraka Investment Company bought Hargrave Securities, a licensed deposit taker, and converted it into an Islamic bank. This served the British Muslim community to a limited extent, but its main client base was Arab visitors of high net worth who spent the summer months in London.

Its business expanded from 1987 when it opened a branch on the Whitechapel Road in London, followed by a further branch on the Edgeware Road in 1989, and a branch in Birmingham in 1991, as by then the bank had between 11,000 and 12,000 clients. It offered current accounts to its customers, the minimum deposit being £150, but a balance of £500 had to be maintained to use cheque facilities, a much higher requirement than that of other United Kingdom banks.

These conventional banks usually allow current accounts to be overdrawn, although then clients are liable for interest charges, which Al Baraka, being an Islamic institution, did not levy.

Al Baraka also offered investment deposits on a mudarabah profit sharing basis for sums exceeding £5,000, with 75 percent of the annually declared rate of profit paid to those deposits subject to three months notice, and 90 percent paid for time deposits of over one year. Deposits rose from £23 million in 1983 to £154 million by 1991.

Initially much of Al Baraka's assets consisted of cash and deposits with other banks, which were placed on an Islamic basis, as the institution did not have the staff or resources to adequately monitor client funding. Some funds were used to finance commodity trading through an affiliate company, as Al Baraka was not a specialist in this area.

Al Baraka's major initiative was in housing finance, as it started to provide long-term Islamic mortgages to its clients from 1988 onwards. Al Baraka and its clients would sign a contract to purchase the house or flat jointly, the ownership share being determined by the financial contribution of each of the parties.

Al Baraka would expect a fixed pre-determined profit for the period of the mortgage, the client making either monthly or quarterly repayments over a 10 to 20 years period, which covered the advance plus the profit share.

There was some debate if the profit share could be calculated in relation to the market rental value of the property, but this was rejected, as frequent revaluation of the property would be expensive and administratively complicated, and given the fluctuating prices in the London property market, there would be considerable risk for the bank.

Although Al Baraka provided banking services in London, its most profitable area was investment management, and in many respects it functioned more like an investment company than a bank. It lacked the critical mass to achieve a competitive cost base in an industry dominated by large institutions, and the possibility of expanding through organic growth was limited.

In these circumstances when the Bank of England tightened its regulatory requirements after the demise of BCCI the bank decided that it was not worth continuing to hold its banking licence, as it would have meant a costly restructuring of the ownership and a greater injection of shareholder capitals.

Consequently in June 1993 Al Baraka surrendered its banking licence and closed its branches, but continued operating as an investment company from Upper Brook Street in the West End of London.

Depositors received a full refund, and many simply transferred their money to the investment company. This offered greater flexibility, as it was no longer regulated under the 1987 Banking Act but under financial services and company legislation.

THE UNITED BANK OF KUWAIT By the late 1980s there was an increasing demand from the United Bank of Kuwait's Gulf clients for Islamic trade based investment, and the decision was taken in 1991 to open a specialist Islamic Banking Unit within the bank.

Employees with considerable experience of Islamic finance were recruited to manage the unit, which enjoyed considerable decision-making autonomy. In addition being a separate unit, accounts were segregated from the main bank, with Islamic liabilities on the deposit side matched by Islamic assets, mainly trade financing instruments. The unit had its own Shariah advisors, and functioned like an Islamic bank, but was able to draw on the resources and expertise of the United Bank of Kuwait as required.

In 1995 the renamed Islamic Investment Banking Unit (IIBU) moved to new premises in Baker Street, and introduced its own logo and brand image to stress its distinct Islamic identity. Its staff of 16 in London included asset and leasing managers and portfolio traders and administrators, and by the late 1990s investment business was generated from throughout the Islamic World, including South East Asia, although the Gulf remained the major focus of interest.

Assets under management exceeded $750 million by the late 1990s, just prior to the merger with Al Ahli Bank, which resulted in the bank being renamed the Al Ahli United Bank. After Al Baraka pulled out of the Islamic housing market the United Bank of Kuwait entered the market in 1997, with its Manzil home ownership plan based on a murabahah instalment structure. A double stamp duty was incurred on murabahah transactions, firstly when the bank purchased the property on behalf of the client, and secondly when it resoled the house to the client at a mark-up.

This was felt by many in the Muslim community to be discriminatory, and following effective lobbying by the Muslim Council of Britain, and a report by a committee charged with investigating the issues, the double stamp duty was abolished in the 2003 budget, with the change taking effect from December of that year. The double stamp duty also applied to the Ijara mortgages introduced under the Manzil plan in 1999.

THE ISLAMIC BANK OF BRITAIN The development that has attracted the greatest interest in recent years has been the establishment of the Islamic Bank of Britain. It had long been felt by many in Britain's Muslim community, especially since the withdrawal of Al Baraka from the retail Islamic banking market, that the United Kingdom should have its own exclusively Islamic Bank.

A group of Gulf businessmen, with its core investors based in Bahrain, but with extensive business interests in the United Kingdom, indicated that they were prepared to subscribe to the initial capital of £50 million. A business plan was formulated in 2002, and a formal application made to the Financial Services Authority (FSA) for the award of a banking licence.

The FSA was well disposed towards the application, indeed its staff charged with regulating the London operations of banks from the Muslim World were knowledgeable about Islamic banking and believed that in a multicultural and multi-faith society such as that of Britain in the twenty first century, Islamic banking was highly desirable to extend the choice of financial product available to the Muslim community.

There was no objection to the new bank being designated as Islamic, as this was not felt to be a sensitive issue in the UK, unlike in some countries where there are large Christian populations such as Nigeria, where the terms Muslim and Islamic cannot be used to designate banks. In Saudi Arabia, a wholly Muslim country, the term Islamic bank also cannot be used, as the major commercial banks and many Shariah scholars object to religion being used as a marketing tool.

The major concern of the FSA was that the new Islamic bank should be financially secure by being adequately capitalised, and that the management had the capability to adhere to the same reporting requirements as any other British bank. The emphasis was on robustness of the accounting and financial reporting systems, and in proper auditing procedures being put in place.

Systems of corporate governance were also scrutinised, including the responsibilities of the Shariah advisory committee, and their role in relation to the management and the shareholders of the Islamic Bank of Britain. The FSA cannot of course provide assurance of Shariah compliance, as that is deemed to be a matter for the Islamic Bank of Britain and its Shariah committee.

However the FSA wishes to satisfy itself that the products offered are clearly explained to the clients, and that full information on their characteristics is provided in the interest of consumer protection.

The Islamic Bank of Britain opened its first branch on the Edgeware Road in London is September 2004, less than one month after regulatory approval was given. Its operational headquarters are in Birmingham, where costs are lower. It has already opened two further branches in London, in Southhall and the Whitechapel Road, as well as branches in Birmingham, Leicester and Manchester, with further branches planned for later in 2006, including Leeds and Bradford in the north of England.

The size of the Muslim population in the immediate locality is one factor determining the choice of branch location, the socio-economic status of the potential clients being another factor, as middle class Muslims in professional occupations with regular monthly salaries are obviously more profitable to service than poorer groups.

The bank stresses the Islamic values of faith and trust, as these are fundamental, but it also emphasises value and convenience, the aim being to have standards of service and pricing at least comparable with British conventional banks.

The opening of the first branch attracted much media attention, and therefore free publicity for the bank. The bank has a well designed website to attract business, and plans to offer on-line services in the future, and has produced informative and attractive leaflets and other publicity material outlining its services.

All the material at present is in English rather than Urdu or Arabic, as the costs of translation and printing have to be seen in the context of promotional benefits. Some staff members are fluent in Urdu and Arabic, but at varying levels of proficiency, and foreign language ability is not a pre-requisite for appointing staff, but good English is important. Many staff members have previous banking experience, and most, but not all, are Muslim.

The Islamic Bank of Britain offers current, savings and treasury accounts, all of which are Shariah compliant. No interest payments or receipts are made with current accounts, but a cheque-book and a multi-functional bankcard is provided, these initially being simply cheque guarantee cards. Savings accounts operate on a mudarabah basis with £1 being the minimum balance.

Profits on savings accounts are calculated monthly and were initially at 3 percent but were subsequently reduced to 2.5 percent, the current rate. No notice is required for withdrawals from basic savings accounts, which in other words can be designated as instant access accounts. Term deposit savings accounts, which are subject to a minimum deposit of £5,000, pay higher rates.

In February 2006 deposits for one, three or six months earned 3.25 percent, 3.50 percent and 3.75 percent respectively, these having being reduced by 0.25 percent from the initial amounts offered. Unique amongst Islamic banks, the Islamic Bank of Britain offers treasury deposits, with a minimum £100,000 for 1, 3 or 6 months being invested.

These operate on a murabahah basis, with funds invested on the London Metal Exchange. This type of account in other words replicates for the retail market the type of wholesale or interbank deposit facilities first operated on a Shariah compliant basis in London in the early 1980s.

The Islamic Bank of Britain offers personal finance, with amounts ranging from £1,000 to £20,000 made available for 12 to 36 months. This operates through Tawarruq with bank buying Shariah compliant commodities that are sold to client on a cost plus profit basis.

The client's agent, who is conveniently recommended by the bank, in turn buys the commodities and the proceeds are credited to the client's account. The client then repays the bank through deferred payments. No home finance is offered, but vehicle finance was made available in 2005.

(To be concluded)

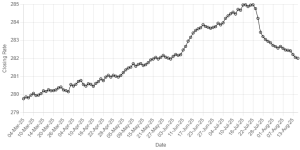

BR100

15,103

Increased By

140.9 (0.94%)

BR30

42,619

Increased By

540.8 (1.29%)

KSE100

148,196

Increased By

1704.8 (1.16%)

KSE30

45,271

Increased By

438.2 (0.98%)

Comments

Comments are closed.