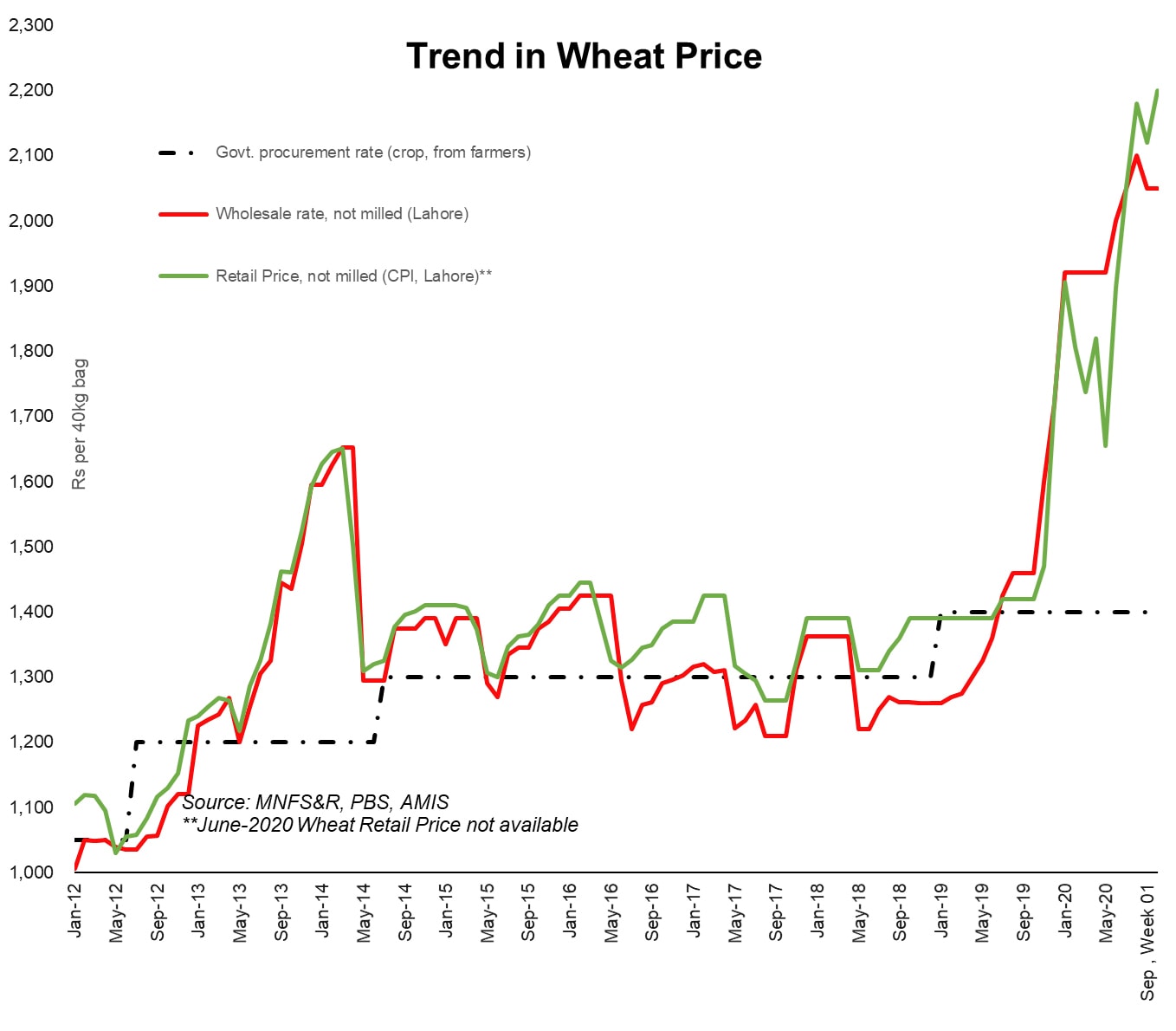

Over the past 10 weeks, wheat flour prices in Lahore have declined by almost one-fifth. Timely release of wheat by provincial food department has been widely credited for bringing the prices under control in the province. Yet, price of raw material wheat has failed to follow in lockstep. What is going on?

Punjab government has taken several measures in commodity price reporting that encourage transparency in data sharing. These include weekly and monthly data reporting by Agriculture Marketing Information Service (Directorate of Agriculture), along with the development of mobile apps such as “Qeemat Punjab” that shares updated grain prices daily.

Measures taken to achieve increased transparency, are of course, commendable developments. Yet, price data collated from various official sources indicate that the reported numbers are increasingly becoming a poor reflection of ground realities. Poor reporting has become particularly misleading in the case of wheat and flour, Pakistan’s staple food sources. Consider the following.

A review of weekly and monthly reported SPI and CPI prices for 7 major cities in Punjab – Gujranwala, Sialkot, Lahore, Faisalabad, Sargodha, Multan, and Bahawalpur, and excluding twin city of Rawalpindi - reveals that price of wheat flour bag remains eerily constant across all provincial urban centres during months of February, March April and May at Rs 805 per 20kg bag. While optimistic commentators may attribute this to effective price control measures adopted by district administration, it is hard not to notice that something is amiss.

Consider that this price stability on paper appeared at a time when the country was in the throes of a wheat flour crisis which had led to establishment of an FIA led inquiry commission on the matter. Also consider that during this period, average price of wheat flour in Islamabad-Rawalpindi increased from Rs 840 to Rs 905 per 20kg bag. Moreover, officially reported prices did not even budge in May 2020, once grain from the then freshly harvested crop began to flow into the commodity market.

Most importantly, between March and April, retail price of wheat (as reported by SPI) was 10 percent lower than wholesale price quoted by AMIS. Thus, official quarters could only keep a lid on reported figures for so long. After the strike of flour mills association, word regarding non availability of flour on official DC rates began to trickle into prime-time news and reported figures in subsequent months began to reflect an upward adjustment.

Ever since, announcement of duty-free wheat import by both TCP and private sector has once again sent wheat price spiral to the back burner of 9 o’clock news. According to MNFS&R, shipments of imported wheat were anticipated to have docked at Karachi port by August end, however, untimely rains may have delayed release to market by a week or two. Wheat price spiral may have after all become a distant memory. Yet, price anomaly in reported data from Punjab is once again becoming apparent.

After declining by 20 percent in the second week of July, wheat flour bag prices in 7 major cities of Punjab have remained constant at Rs 860 per 20kg for the past 9 weeks. During the same period, average price in provincial capitals of Quetta and Karachi has increased by over 10 percent, with higher increases in smaller towns in the interiors of those provinces.

While variance in prices between provinces is not out of ordinary and may also be seen as evidence of market forces at work, consider that wholesale price of raw material wheat in Lahore and other cities of Punjab as reported by AMIS is once again higher than the retail prices reported by PBS based CPI. But most strikingly, retail price of wheat (not milled) for the past four weeks is 20 percent greater than retail price of wheat flour (milled), where both figures are as reported by PBS based weekly SPI.

Higher price for raw material wheat (not milled) versus that of processed flour is not only anomalous based on historic trends, the movement of prices over the past several months has also been very erratic, devoid of any trend. Yet, that is still not the greatest oddity of all.

Consider that during the months when price of wheat flour (as reported by PBS) was constant across major cities in the province, weekly average, minimum and maximum prices in each of those cities was also peculiarly same. This means that not only were the average prices across all cities are same, as are minimum and maximum prices within and across the province.

If that is the methodology officially adopted by provincial price control authorities, then by all means; moreover, there should be no reason to point fingers at reported data. However, not only are these prices not a reflection of prices on the ground – as confirmed by various news reports – the methodology employed suddenly changes beginning mid-May and through June, when average prices across cities, as well as minimum and maximum prices both within and across cities shift to a free-range instead of constant figures.

While the sudden change may be hard to digest, a revision in price reporting methodology is very much lawful. Yet, the comedy of errors refuses to stop. As noted earlier, beginning second week of July, prices across towns in Punjab once again find common ground, becoming constant for the following 9 weeks (till date).

For most part, this may appear to be no more than an attempt by provincial authorities to portray success in bringing commodity price spiral in control under their administration. However, it also points to an uneasy conclusion that components in PBS reported price data are grossly misrepresented. Moreover, because PBS’ data collection methodology as far as other provinces are concerned involves market surveys, the methodology employed across the country also comes under scrutiny for its inconsistency.

Readers may note that wheat and wheat flour have a combined weight of just 3.6 percent in urban CPI, and as such under reporting for one province may not be highly consequential for inflation index. However, the combined weight of two commodities goes up to 7 percent in rural CPI basket. Also note that this finding relates to only one out of 28 food group commodities, whereas “constant prices anomaly” has become a recurrent feature across various commodities especially for Punjab. Both researchers and regulators may benefit from taking a closer look on the subject by putting reported numbers through more scrutiny.

Comments

Comments are closed.