As the economy rebounds from last year’s Covid shock, recent trade and current account deficit numbers are creating some concerns about Pakistan’s external sector outlook. The widening of these deficits since the summer has indeed been somewhat faster and larger than initially anticipated. In Pakistan, such developments have historically been harbingers of a painful economic bust, so it is not surprising that some are reacting nervously. However, there are strong reasons to believe that, unlike previous such episodes, this one will be manageable.

Diagnosing the rise in the trade deficit

While exports and remittances have been strong so far this year, the current account deficit has increased due to a sharp rise in imports. The import bill has risen to $32.9 billion during July-November this year, based on PBS data, compared to $19.5 billion during the same period last year.

Higher global prices explain much of the rise in the trade deficit of $10.9 billion over this period. Around three-fifths of this increase ($6.6 billion) is estimated to stem from the sharp rise in global commodity prices and shipping charges, as global demand recovers from Covid amid supply chain disruptions (Figure 1); while about two-fifths ($4.3 billion) of the rise in the trade deficit is attributable to stronger domestic demand, as the Pakistan economy recovers from Covid. In Pakistan, there is a strong historical correlation between global commodity price movements and import growth (Figure 2).

Indeed, Pakistan is not alone. These factors have also contributed to the sharp deterioration in the current account position of most commodity-importing emerging markets (Figure 3).

Global commodity prices should normalize and one-off imports will diminish

The first reason that anchors the stability of the external outlook is that the large price increases in global commodity prices and food items which have inflated imports in recent months are expected to eventually wane. There exists well-known cyclicality in commodity prices, with a tendency to revert to their average levels after some time (Figure 4).

Looking ahead, with around one-fourth of Pakistan’s imports accounted for by energy, a relatively inelastic commodity, future developments in prices will have a heavy bearing on this part of the import basket.

The good news is that based on previous oil price cycles and futures prices, these are likely to start coming down over the rest of the fiscal year. As in past cycles, this is likely to happen due to both a supply and demand response. Supply chain constraints should ease as disruptions associated with Covid normalize, while demand is likely to moderate as central banks around the world tighten monetary policy somewhat faster than expected in response to higher inflation out-turns. A sustained $5 per barrel decline in oil prices reduces Pakistan’s import bill by around $1 billion in a year.

Indeed, global commodity prices, including oil, have already seen a marked decline in recent days amid concerns that global demand could be affected by the new Coronavirus variant, Omicron, as well as signals of faster monetary policy normalization from the Federal Reserve.

At the same time, imports of food items, in particular sugar and wheat, are also expected to diminish through the rest of the year given the strong outlook for agricultural output in Pakistan for this fiscal year.

A proactive policy response

The second reason for optimism is that the policy response to moderate domestic demand has been more timely than before and the exchange rate is helping to moderate rather than fuel external pressures (Figure 5).

The most recent episode of a sustained current account deficit increase starts in December 2015, when the monthly current account crossed $700 million. Then, it took a full twenty-five months before policy rates were raised and nineteen months before the rupee was allowed to adjust by even a few paisas, by which time the economy was already at an advanced stage of overheating.

In the meantime, the SBP’s foreign exchange reserves had begun to fall precipitously, sowing the seeds of their eventual near depletion and the full-blown balance of payments crisis that followed.

By contrast, this time around, within only four months of the monthly current account crossing the same threshold in May 2021, policies began to be adjusted. The policy rate was raised in September and has already risen by a cumulative 175 basis points, while the exchange rate has depreciated by around 12 percent. Instead of falling like last time, SBP’s foreign exchange reserves have actually increased by around $3 billion.

Thus, the policy landscape could not be more different, and action is being taken early to ensure that the economy does not overheat and external imbalances are not entrenched.

Additional measures have also been taken to moderate the current pace of demand growth to a more sustainable level, including by curbing consumer finance through tighter macro prudential regulations. Together, these proactive measures will moderate the growth of imports going forward and allow a faster correction in the current account deficit.

This changed policy environmentis part of a fundamental improvement in the way that the economy is being managed, which reduces external vulnerabilities and facilitates sustainable growth. Unlike the past, foreign exchange reserves are no longer being sacrificed in defense of an overvalued exchange rate that causes the current account deficit to keep growing by subsidizing imports and penalizing exports.

The flexible and market-determined exchange rate in place since July 2019 now reflects supply and demand of foreign currency created by exports, remittances, and imports. In so doing, rather than compounding the problem, the exchange rate acts as a natural moderator on the size of the current account deficit and allows precious foreign exchange reserves to be protected. Through both of these effects, it helps prevent a boom-bust cycle of the kind that we have seen so many times in Pakistan.

Healthy foreign exchange reserves and a fully-financed external position

The third factor that should ensure external sustainability in Pakistan is that, despite a larger current account deficit than initially anticipated, foreign exchange reserves are expected to continue to remain adequate – instead of plunging to $7 billion as in the aftermath of the last episode of current account weakening – as external financing needs are more than fully met.

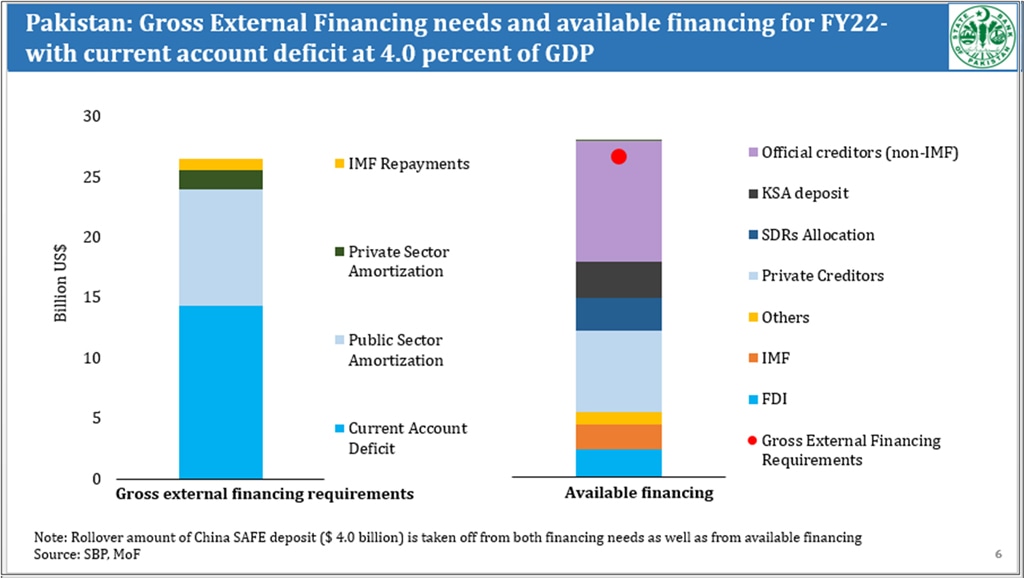

All told, the current account deficit is likely to be closer to 4 percent of GDP in FY22. As a result, Pakistan’s external financing needs, defined as the sum of the current account deficit, short-term debt and medium and long-term debt coming due during the fiscal year, will be around $26 billion.

The important thing to note is that despite this slightly wider current account deficit, available sources of external funding are more than enough to meet our external financing needs in FY22 (Figure 6).

In addition to previously anticipated commercial, bilateral and multilateral funding, this includes an additional $4.2 billion arranged from Saudi Arabia in the form of an FX deposit and an oil financing facility.

Vaccine imports are also now being financed by funding arranged through ADB and the World Bank. As a result, Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves should remain at adequate levels through the rest of the year, and begin to resume their growth trend once global commodity prices ease and import demand growth moderates.

In closing, we are confident that the current pressures on Pakistan’s external accounts will be successfully managed.

In the past, there were three warning signs that pointed to an escalation of balance of payments problems and eventual bust: (i) delayed macroeconomic adjustment to prevent overheating, (ii) an exchange rate that was not allowed to adjust to restore balance between demand and supply of foreign currency, and (iii) falling FX reserves in defense of the currency and amid inadequate external financing. None of those warning signs is visible today.

The policy response to arrest the deterioration in the current account deficit has been considerably more timely than in the past. In addition, exogenous factors propping up the current account deficit, notably high global commodity prices and temporary food imports, should also diminish through the rest of the year. Finally, the external position is fully financed, such that Pakistan will be able to comfortably meet its external financing needs and foreign exchange reserves will continue to rise.

The writer is former Deputy Governor, State Bank of Pakistan

He tweets @MURTAZAHSYED

Comments

Comments are closed.