More than half of Pakistan’s 241 million citizens are under the age of 19. Every year, millions of them join the workforce—only to find the industrial economy moving in the opposite direction. If there was ever a recipe for demographic disaster, this might be it.

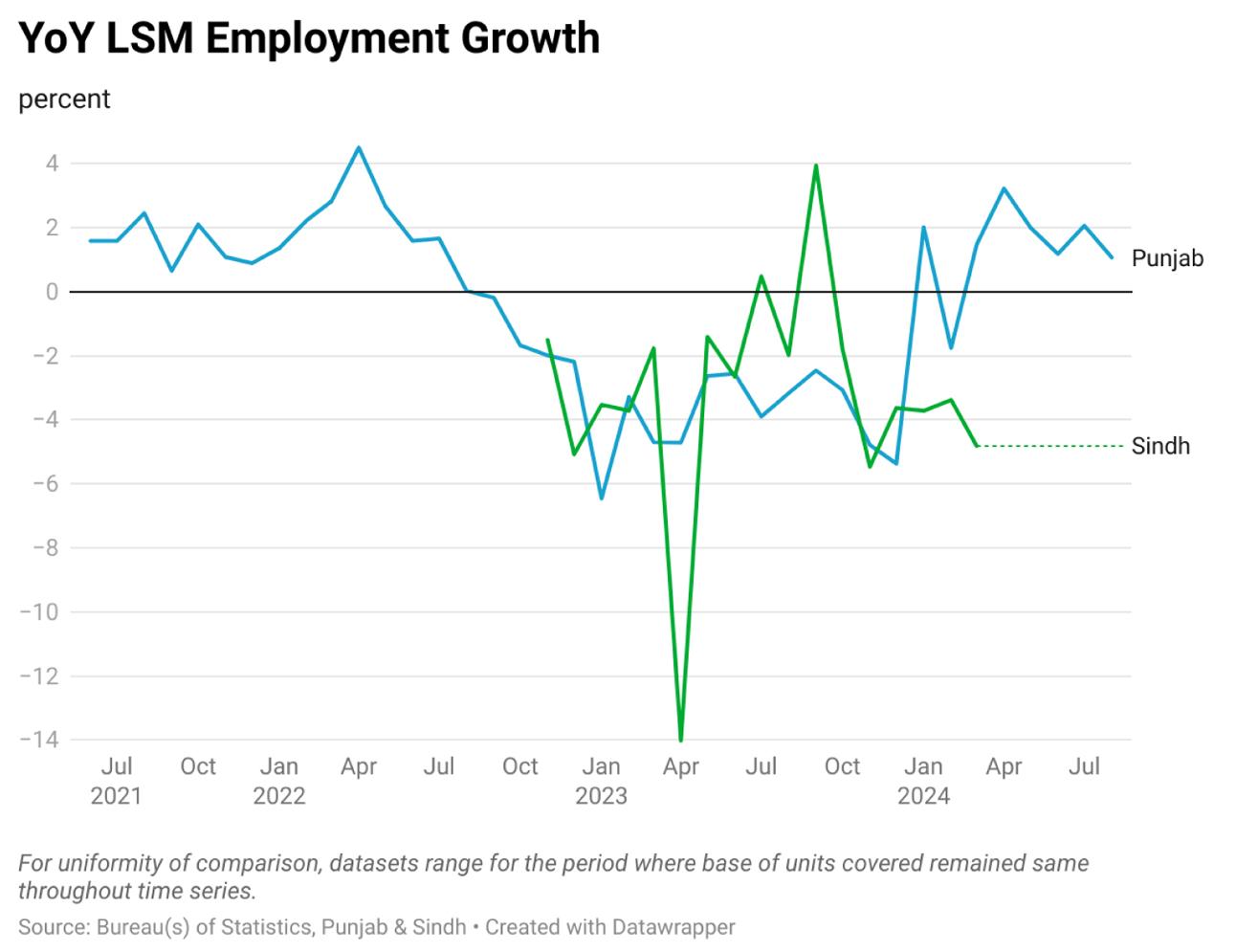

The employment data from Punjab and Sindh’s large-scale manufacturing (LSM) sector paints a bleak picture. In Punjab, employment has declined steadily from an index value of 100 in July 2022 to 96.3 by June 2024. Sindh has done worse - falling to 95.4 over a similar period. This isn’t seasonal fluctuation—it’s a structural decline. And it’s happening at a time when Pakistan should be expanding industrial output just to keep pace with its youth bulge.

And these aren’t fringe numbers either. In Punjab, the data covers 72 percent of the province’s LSM value-added. For Sindh, the coverage is even higher at 84 percent. Put together, this suggests that employment opportunities have either stagnated or declined across at least three-fourths of the country’s large-scale manufacturing. It’s unlikely the remaining quarter has been marching to a different, rosier beat.

But the factories aren’t humming. They’re slowing, stalling, or, in some cases, shutting down. Large manufacturing has been in the doldrums for over two years, and in many sectors, output is now lower than it was 5–7 years ago. The oft-cited concern that Pakistan is deindustrializing prematurely is no longer a cautionary tale. It’s a live reality.

True, LSM isn’t the whole economy. Construction, retail, and wholesale—sectors that employ millions—aren’t reflected here, and employment numbers for these are patchy at best. Small-scale industries, often more labour intensive, are also missing. But LSM still accounts for a significant chunk of value addition, and with data available on a time series, it remains a useful proxy for overall employment health. And that health is clearly deteriorating.

In more advanced economies, jobs data are treated with the gravity of GDP or inflation numbers. In Pakistan, they’re often relegated to footnotes and forgotten until the next crisis. Yet employment is a crucial input into understanding the output gap—how much potential the economy has and how much it’s actually producing.

That gap seems to be widening. This brings us back to the young population: if jobs don’t keep pace with the workforce, what comes next? Idle labour, wasted potential, social unrest?

Unless industry, government, and academia collaborate to align skill supply with actual demand, Pakistan risks squandering its biggest asset—its people. And with charts like these, the squandering has already begun.

Comments