On 2 April 2025, the United States introduced a two-tier tariff regime comprising a 10 per cent universal baseline tariff and elevated country-specific tariffs of up to 50 per cent, targeting 57 countries—including many in the Asia-Pacific—with limited exemptions. Although the country-specific tariffs were suspended on 9 April for all but China, policy uncertainty remains.

Subsequent signals have been mixed: while product exemptions were expanded to include certain electronics, the US also launched new Section 232 investigations into imports of semiconductors and pharmaceuticals. These developments suggest the potential for further unilateral trade actions and underscore the persistent uncertainty in the global trade environment.

These shifting trade dynamics carry important implications for the Asia-Pacific region, where deep integration into global value chains (GVCs)—characterized by high reliance on imported inputs—intensifies both direct and indirect exposure to evolving US tariff measures.

Direct exposure occurs when a country’s exports to the US are directly subject to tariffs. Countries most at risk from direct exposure were identified in our earlier blog. However, the actual burden can be heavier than the announced tariff rate. This is because tariffs are applied to the full shipment value, even when much of it comes from imported inputs.

As a result, the cost falls disproportionately on the exporter’s own, smaller share of value-added. For example, only $51.5 of Cambodia’s $100 textile shipment to the US is domestically produced.

A 10 per cent tariff on the full value translates into an effective 23 per cent tax on Cambodia’s actual contribution. In fact, analysis using ESCAP’s RIVA (Regional Integration and Value Chain Analyzer) shows that while most Asia-Pacific economies are subject to the same 10 per cent baseline tariff, many face an effective tariff burden exceeding 15 per cent (figure 1).

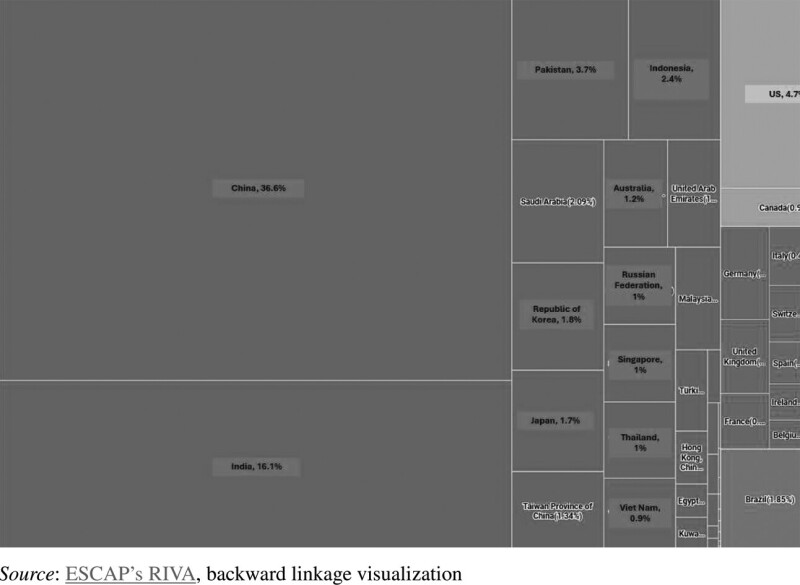

Indirect, or pass-through, exposure arises when a country exports intermediate goods or services that are later embedded in another country’s exports to a tariff-imposing market. For example, in 2022, Bangladesh exported approximately USD 8.2 billion in textiles and textile products to the United States, with about one-third of that value derived from upstream trade partners. Notably, US firms themselves, along with firms in China, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia, are key contributors to Bangladesh’s textile exports—making them indirectly exposed to US tariffs on those exports (figure 2).

The impact of US tariffs is expected to vary widely across the Asia-Pacific region. Economies with high direct export exposure—such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand—could face significant trade-related contractions, with direct exposure accounting for 3 to 11 per cent of GDP if the April-2 tariffs were reinstated (table 1).

Indirect exposure through GVCs may also dampen growth in upstream economies supplying raw materials, parts, and components. For example, Brunei Darussalam, Mongolia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, and Singapore could see indirect exposure equivalent to approximately 1 per cent of GDP. In contrast, economies with larger domestic markets or more diversified export structures—particularly those with strong services sectors—are better positioned to absorb the trade shock.

Targeted support and policy coordination are key

For both policymakers and industry leaders, identifying the source of vulnerabilities is essential for crafting targeted and forward-looking responses. These strategies should not only aim to mitigate current risks but also strengthen long-term economic adaptability.

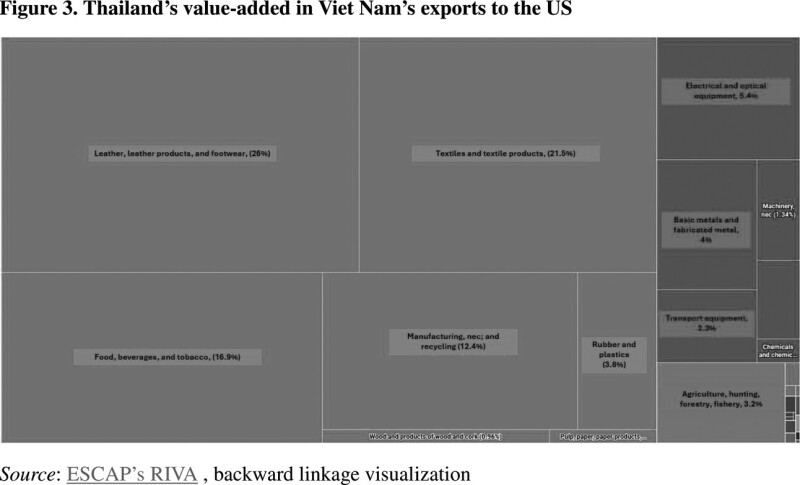

Evidence-based analysis is essential for guiding targeted support. Sectoral data highlights how Thailand, for example, is indirectly impacted through its upstream supply chain linkages with Vietnam. The following Thai manufacturing sectors are identified as the most vulnerable: Leather and Textiles, Food and Beverages, other Light Manufacturing, Electrical Equipment (figure 3). This insight suggests that coordination between Thailand and Vietnam focusing on these industries could mitigate shared risks and enhance resilience.

Beyond bilateral efforts, regional coordination with supply chain partners is essential to address short- to medium-term challenges. This is particularly important because:

-

Relocating supply chains requires long-term planning guided by infrastructure, labor, innovation capacity and regulatory stability—not just short-term tariff shifts.

-

Strategic uncertainty remains high. No country is fully shielded from tariff exposure. In the current unpredictable global trade environment, firms will remain cautious about investing or reconfiguring supply chains.

Governments across the Asia-Pacific must be prepared to deliver tailored support to firms and workers as GVCs continue to evolve. Informed domestic and international policies require sector-specific assessments. In this context, ESCAP’s TINA tariff simulator offers a valuable tool for preliminary assessment of Asia-Pacific tariff exposure at the HS 6-digit level.

In addition to the recommendations in our earlier blog, policy priorities may include:

-

Targeted support for affected SMEs and export-oriented firms

-

Reskilling and adjustment support for impacted workers

-

Incentives to diversify exports and reduce market concentration

-

Bilateral and regional cooperation to maintain supply chain continuity.

Copyright Business Recorder, 2025

Witada Anukoonwattaka is Economic Affairs Officer, ESCAP

Yann Duval is Chief of Trade Policy and Facilitation Section, ESCAP

Rupa Chanda is Director of Trade, Investment and Innovation Division, ESCAP

Comments