Mohamed Rasool was over the moon when he became father to twins - a boy and a girl - a year ago. The trucker in his 40s celebrated by firing shots in the air, distributing chocolate among kids and inviting friends to a lavish dinner in Mashookhel, a dusty, sleepy town in north-western part. He named his daughter Kainat, which means universe. In a first tragedy, Rasool's son died at just 9 months old, but he says Kainat's gleeful smiles carried the family through the shock.

In autumn Rasool had another jolt: Kainat was diagnosed with polio, a disease that can cripple children for life. "She is gone ... my little angel is finished," the distressed father said, trying to hold back tears and being comforted by relatives. "Sometimes I can't look at her," Rasool said, his head bowed in grief. "When I think that she won't be able to walk, play like normal kids and nobody will love her, marry her when she grows up, it hurts me."

The polio virus invades the nervous system, and can lead to irreversible paralysis and in some cases death. His "universe" was "shattered and ruined," Rasool said, well aware that Kainat's illness was influenced by factors far beyond his control. Mashookhel is on the edge of the north-western city of Peshawar in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, bordering the country's tribal badlands.

The region was controlled by Islamist militants linked with al Qaeda and its allied Taliban until they were chased out by a series of concerted military offensives since June 2014. The conflict had a critical effect on a long-term vaccination project to eradicate polio from Pakistan, which along with Afghanistan is one of the last two countries where the disease is still endemic.

"They (militants) banned vaccination in this town for two years," health worker Arshad Khan said as he drove around Mashookhel. "It is only now that we are back to work." The first vaccinators returned to the small town of some 40,000 people in March. "There are some fears that militants can come back," said Khan, "but overall there is a lot of improvement."

Khan, who leads a team of World Health Organisation workers in Mashookhel, has experienced the dangers close-up. A year ago, two of his female colleagues were gunned down just 5 kilometres away. Around 50 vaccinators and police guarding them have been killed in the last year across the country, especially in the north-west and Karachi. "Attitudes have changed," Khan said. "Those who were opposing the vaccination are finished."

In Peshawar city, clerics who previously opposed vaccination because they thought it was against Sharia are all silent now. The government has been showing zero tolerance against hate speech and opposition to polio vaccination since Taliban gunmen killed 136 children at a school in Peshawar last year, in an attack that shocked the whole country. According to police records, 151 people have been arrested in the north-western province for inciting violence and opposing vaccination since the school massacre. "It looks the state is flexing its muscles, and it is working," said Fida Khan, a security analyst based in Peshawar.

The Taliban and like-minded Islamic clerics told followers that the vaccine contained a substance that sterilises men and is a conspiracy by the West to reduce the number of Muslims. They also cited the case of a Pakistani doctor who ran a fake vaccination campaign for the CIA to help trace al Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden. But it seemed fewer people were falling for the propaganda now, said Senator Ayesha Raza Farooq, head of Pakistan's anti-polio programme. The number of newly infected children nation-wide peaked at 306 in 2014, according to Farooq.

Far fewer parents are refusing the vaccine, while the number of newly infected children so far this year is less than 40, the polio chief said. In Rawalpindi city near Islamabad, Nasir Majeed brought his 1-day-old daughter to Benazir Bhutto Hospital for vaccination. "I'll always get my kids vaccinated," said the 33-year-old motorbike dealer, "I don't believe in what the mullahs have been saying."

Nadeem Ahmed Khan, a vaccinator at the hospital's children clinic, said around 150 parents bring their kids for vaccination every day despite the fact that mobile teams visit every household. "If some kid doesn't get the vaccination, parents bring them here," Khan said. "People don't want to take any risks."

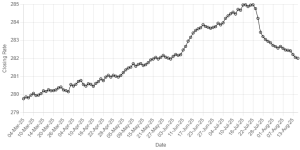

BR100

15,186

Increased By

82.6 (0.55%)

BR30

42,842

Increased By

223 (0.52%)

KSE100

149,361

Increased By

1164.3 (0.79%)

KSE30

45,552

Increased By

281.7 (0.62%)

Comments

Comments are closed.