In the historical perspective, the Muslim League Lucknow session (1937) witnessed the successful culmination of Jinnah's untiring efforts to unite Muslims on one political platform; it also represented the first breakthrough in his attempts to revitalise and reorganise the Muslim League as the political spokesman of Indian Muslims.

Lucknow electrified and enthused the Muslim masses as nothing else had done before: it also produced immediate results. Within three months, some 90 new branches were set up and about 100,000 new members were enrolled in the United Provinces alone. Within a week of his return to Lahore, Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan, the Punjab Premier, wrote to Jinnah, that

"...enrolment of the League members is going apace and we hope to be able to set up district Leagues throughout the province in a short space of time... I have instructed all the Muslim Unionist members to start enrolling Muslims in their ilaqas [localities] and I am receiving very promising and satisfactory reports from the various parts of the province. On the whole, the development at Lucknow which brought about the solidarity of the Muslims throughout India has been welcomed by the Muslim masses..."

Sikandar's letter was followed by the setting up of some 40 branches in about two months. Jinnah's strategy and drive, patience and perseverance, it seems, were at last bearing fruit, and the Muslims were united as never before.

The spectacular growth of the League under Jinnah's leadership was reflected both in the strength and composition of delegates to the annual sessions and the membership figures in the post-Lucknow era. While the 1933 session had to be abandoned for want of quorum and the quorum itself had to be lowered from 75 to 50 in 1931, the League session in April 1936 was attended by 200 delegates, the figure rising to 2,000 at Lucknow in 1937. The seating capacity of the pandal was 5,003 at Lucknow, 15,000 at Calcutta (special session, April 1938), and over 60,000 at Lahore (1940). Actually, the attendance at Lahore, far in excess of the seating capacity, was estimated at over 100,000 and the session itself has been described as "one of the most representative gatherings of the Musalmans of India".

Likewise, total membership which stood at 1,333 in 1927 showed a phenomenal rise. Madras, with a mere 6 percent Muslim population alone counted 112,078 members in 1941, while Bengal enrolled 550,000 members in 1944 - the figure exceeding "the number ever scored by any organisation in the province, not excluding the Congress". For the same year (1943-44), Sind claimed the enrolment of some 300,000 members, ie, about 25 percent of the adult male Muslim population in the province.

A more sure index to the growing strength of the League was provided by the by-elections in the post-Lucknow period. Between 1st January 1938 and 12th September 1942, it won 46 (82%) out of 56 Muslim seats, as against three seats (about 5%) won by the Congress and seven by independents. Further testimony was provided by the enthusiastic response that Jinnah's call to commemorate 22nd December 1939 as Deliverance Day - ie, deliverance from "tyranny, oppression and injustice" of the Congress raj - elicited throughout the subcontinent.

Even the British, always a little tardy in recognising movements opposed to their imperial interests, could not for long withhold official recognition of the League as the chief spokesman of Muslim India. Although precipitated by other factors, the British recognition finally came in September 1939, when on the outbreak of the war the Viceroy invited Jinnah along with Gandhi for talks.

In a sense, the Lahore session (1940) and the adoption of the "Pakistan" resolution represented the successful completion of Jinnah's mission to galvanise the Muslims on one platform and confirmed his claim to the sole leadership of Muslim India. This claim was further buttressed by his singular success in securing British recognition, though couched in general terms, of the core Muslim demands. For the Viceroy's declaration of August 8, 1940 secured for Muslims virtually the power of veto over the shape of the future constitutional framework. The winning of this crucial assurance, often described as one of Jinnah's greatest triumphs, was later to save the Muslims and the Muslim League from being bypassed at the first Simla Conference in July 1945. On the other hand, the disbandment by the Viceroy of the Conference itself, because Jinnah stoutly refused to stand down his claim to nominate all the members in the Muslim quota of seats (since the League alone represented the Muslims as a whole), amounted to an implied recognition that Jinnah alone was capable of delivering the goods on behalf of Muslims a recognition that was further to enhance Jinnah's prestige, and to gather and to galvanise the still uncommitted Muslim leadership, the Muslim intelligentsia and the masses behind him and the League in the crucial pre-election (1945-46) period.

Although Jinnah's leadership among the Muslims became securely established only after Lucknow, he was regarded even earlier as, to quote Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), "the only Muslim in India...to whom the community has a right to look up for safe guidance through the storm that is coming..." Iqbal's profound faith in Jinnah and his leadership also found expression in his rather fervent hope that "at this serious juncture, your genius will discover some way out of our present difficulties". This explains why, among others, Iqbal who first met Jinnah at the second Round Table Conference (1931) in London, came close to him on his return, writing to him regularly during most of 1936 and 1937. In his letters to Jinnah, he discussed with him at length the political situation in the subcontinent and the burning issues of the day; he identified the long-term and short-term goals of Muslim India and, above all, he urged Jinnah to persevere and persist in his efforts to reorganise the League on a sound and stable basis, to galvanise the Muslims into a power to be reckoned with, and to lend coherence, direction and expression to their innermost urges and cherished yearning. Not only did Iqbal commend "Pakistan" to Jinnah as the supreme solution to the crucial problem of Muslim identity as well as of chronic Muslim poverty in the subcontinent; but a little later, in 1936, he also urged him to come out openly for "Pakistan" as a counter to Nehru's Muslim mass contact campaign, raised on the rather enchanting appeal of bread and freedom. But the practical politician that Jinnah was, he felt that unless and until the Muslims were first united and organised on one platform, the adoption of the Pakistan goal by the League would be rather premature, even self-defeating.

In any case, by 1940 Jinnah was to discover the Muslim soul and give coherence and direction to the Muslims' innermost, but as yet vague, urges and aspirations. Jinnah's efforts to concretise Muslim hopes and fears, as well as the quest for a destiny since 1936, were finally to culminate in the formulation of a viable permanent platform in Pakistan. If Lucknow was a turning point in the careers of both Jinnah and the Muslim League, this represented a watershed. By then Jinnah had arrived - that in a spectacular way, and with a bang as well. He was now a completely changed man: from an "ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity" he had become the fiercest advocate of Hindu-Muslim separation. For, under his inspiration, Pakistan had become Muslim India's "defence", "deliverance" and "destiny". And as a prelude to the new role he was soon to fill in, his own standing with his people underwent a change: he became the Quaid-i-Azam, the supreme leader of Muslim India.

Even so, his assumption of this new role as the supreme and unquestioned leader of Indian Muslims was, as it were, in the nature of an extension, perhaps a logical corollary, of his erstwhile role. Till 1937 Jinnah had concentrated on the sober, cultured minority in the community in the belief that once that politically relevant and socially dominant stratum was won over, the whole community would follow suit almost automatically.

But a number of factors since Gandhi opted for a mass movement in 1919 had made that strategy obsolete; hence Jinnah went in for mass politics at Lucknow. However, underlying all his efforts was the basic concept of ensuring political power to Muslims in India's body politic. And, in seeking power for Muslims and taking up the Pakistan demand, Jinnah had taken up a charismatic goal - a goal, which had not only lain close to their (Muslims') heart ever since they had lost political power to the British, but had also long haunted them.

In essence, then, it is in his bold and enchanting promise to restore political power to Muslim India at a time when it was confronted with a desperate situation that one must really look for the more important of the clues to his spectacular rise and singular success as the supreme leader of Muslims, their Quaid-i-Azam, in the epoch-making decade of 1937-47.

(The writer is HEC distinguished national Professor, has recently edited 'Unesco's History of Humanity', vol. VII, and edited 'In Quest of Jinnah' (2007), the only oral history on Pakistan's founding father)

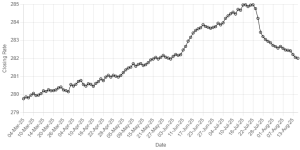

BR100

15,186

Increased By

82.6 (0.55%)

BR30

42,842

Increased By

223 (0.52%)

KSE100

149,361

Increased By

1164.3 (0.79%)

KSE30

45,552

Increased By

281.7 (0.62%)

Comments

Comments are closed.